Many people have tried an online symptom checker: it asks a series of questions (“Where does it hurt?”, “Do you have a fever?”) and then suggests a short list of possible diagnoses.

But there is a problem if we want to trust and test such systems, especially modern AI chatbots and large language models that are unpredictable. We need to find a curated reference, a knowledge base that is consistent and reproducible. The paper behind this post proposes a practical way to build exactly that – a medical knowledge base extracted from a certified source.

The idea behind the paper is to treat the questionnaire called NetDoktor like a giant decision tree, then convert every path through that tree into a clean “if these facts are true, then these diagnoses apply” rule.

Each questionnaire from NetDoktor is identical in structure:

- You start at the first question (what we call the root).

- Each answer sends you to the next question (a branching).

- Eventually you reach an end screen showing suggested diagnoses (the leaves).

If we systematically explore all possible answer combinations, we can reconstruct the full decision tree hidden inside the questionnaire.

The questions and answers are written for humans, not computers. An important next step is to translate natural text in the following manner:

- “Is the skin reddened (in places)?” => a logical statement like reddened_skin or not_reddened_skin, depending on the user’s answer.

- “Select the most affected area” => a single variable chosen option becomes the fact (e.g., head, neck, etc.)

The paper distinguishes two common styles of questions:

- Type 1 (open-ended): where the answer itself becomes the fact, and

- Type 2 (closed-ended): the question defines the fact, and the answer decides whether it is true or false.

Once we have the tree and the extracted logical statements, we can generate rules by walking from the root to every leaf:

- Everything you answered along the way becomes the premise (the “IF’” part).

- The diagnoses at the leaf become the conclusion (the “THEN” part).

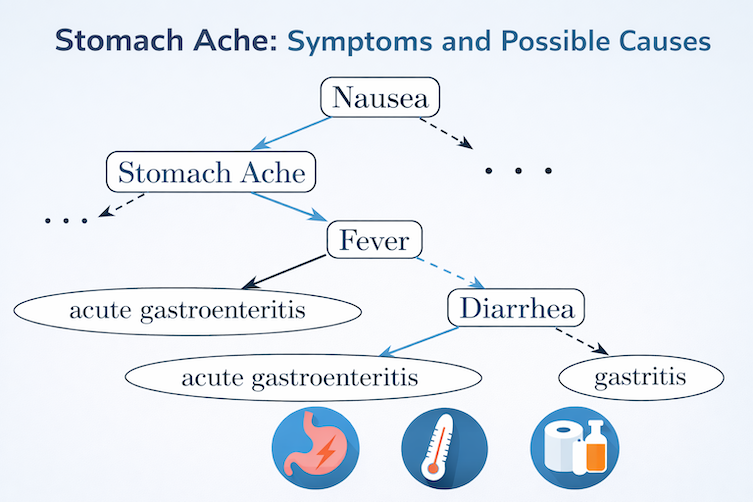

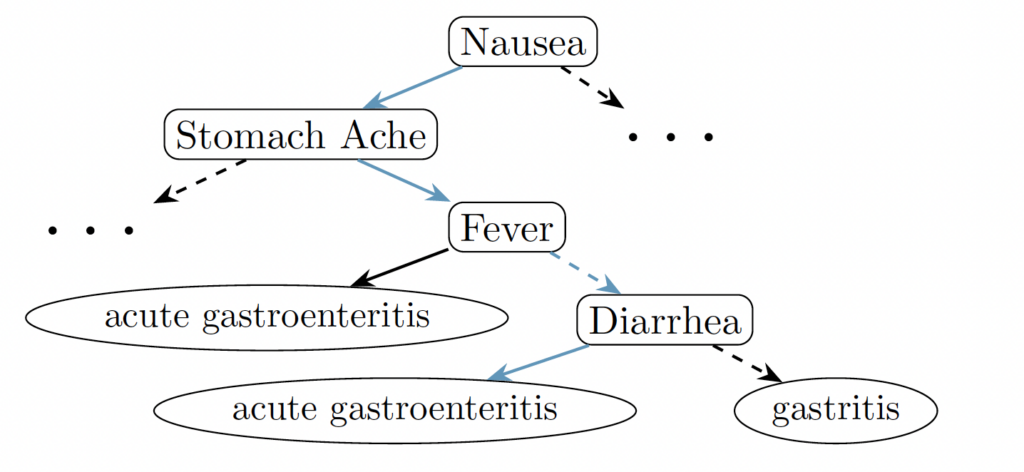

An illustrative example looks like this: If someone has (i) nausea and stomach ache and also (fever or diarrhea), then one possible diagnosis is acute gastroenteritis. If someone has (ii) nausea and stomach ache and no fever and no diarrhea, then one possible diagnosis is gastritis.

We depict the example (i) as a decision tree.

Doing this at scale turns the whole questionnaire into a structured knowledge base that a computer can reason with.

A logic-based knowledge base is useful because it is:

- Explainable: you can trace exactly which answers led to which diagnoses.

- Deterministic: the same inputs always give the same outputs.

- Queryable: you can ask targeted questions like “which diagnoses are possible if we only know these symptoms?”

One especially interesting application in the paper is testing modern AI systems: use this rule-based system as an oracle to evaluate black-box models like LLMs on the same diagnostic tasks.

The paper highlights several challenges and next steps, such as:

- Handling cases where multiple different paths lead to the same diagnosis.

- Removing redundancy when similar subtrees repeat.

- Converting large trees into more efficient internal formats so you can compute things faster (for example, counting how many symptom combinations lead to each diagnosis).

- Going beyond “what diagnosis was suggested” to “what were the sufficient and necessary reasons behind that suggestion” – which can help analyse potential bias in the underlying knowledge base.

The paper’s contribution is a pipeline for extracting expert-curated medical knowledge from an existing symptom-checker and transforming it into a clean, explainable, machine-reasonable set of rules.

In a world where medical AI is getting more powerful and sometimes less transparent, having a method to build understandable, testable knowledge bases from real expert sources is a big step toward safer and more accountable systems.

More can be read in the full paper available in the IS 2025 conference proceedings: https://chatmed-project.eu/knowledge-repository/conference-papers-is2025-ljubljana-slovenia/.